How to write OKRs

Examples and best practices for writing OKRs.

Examples and best practices for writing OKRs.

SubscribeWhat are OKRs?"OKR stands for Objectives and Key Results. It's is a powerful goal-setting and tracking methodology. OKRs help aligns the team and focuses on what matters for the organization. Goal setting, according to OKRs, increases team autonomy and employee engagement and brings a lot of benefits overall."

Example of OKRs

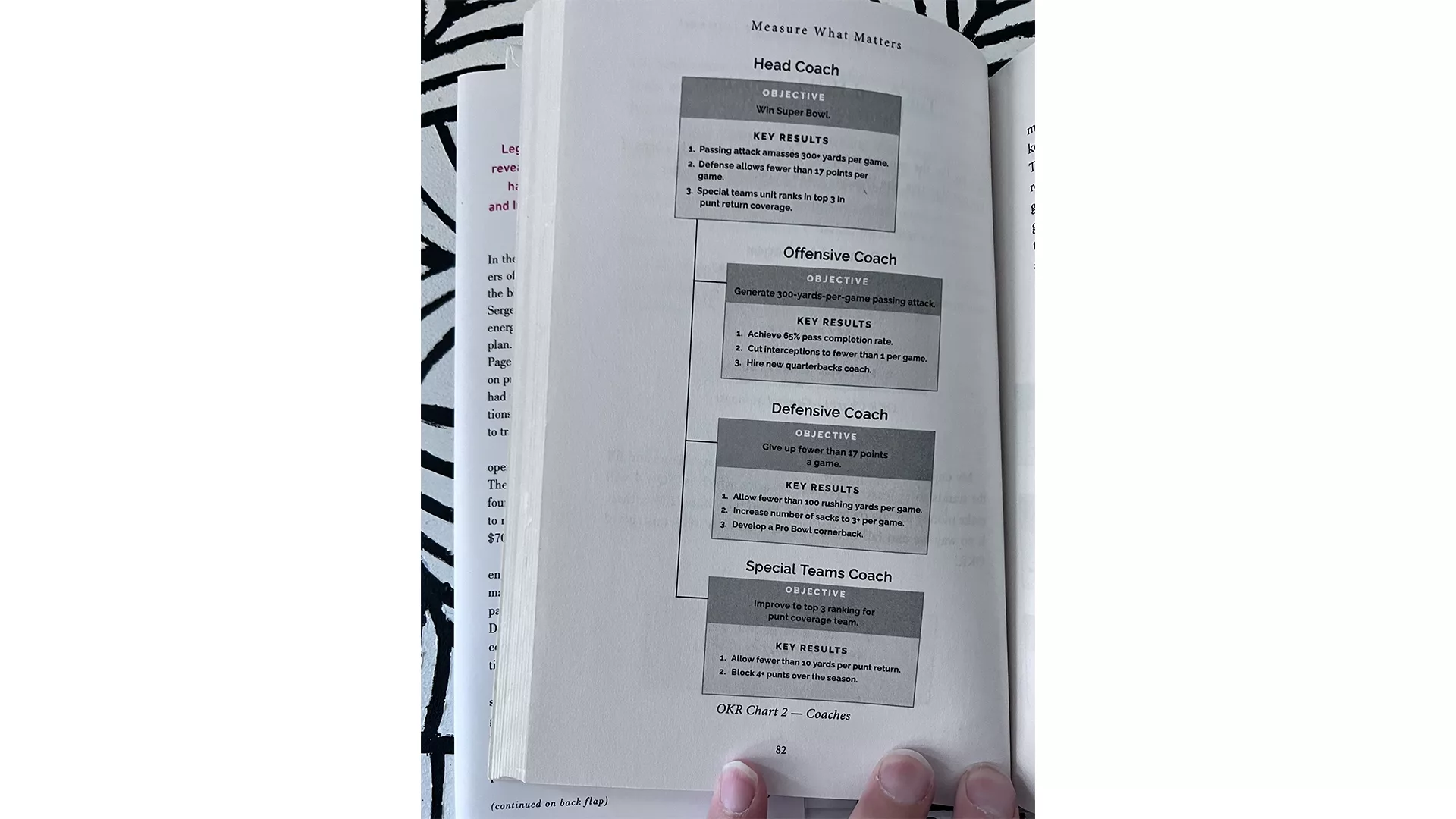

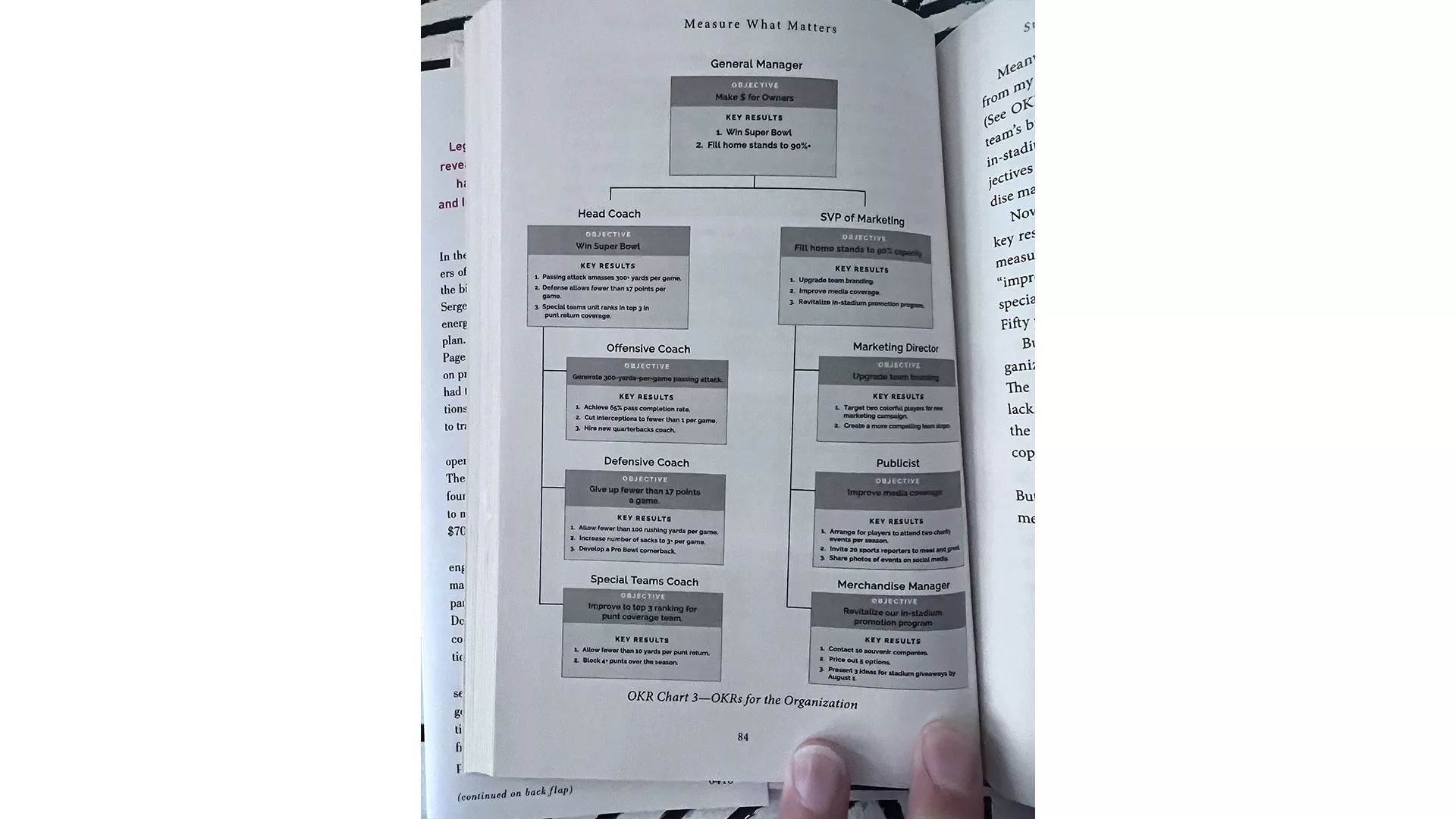

The examples shown below are taken directly out of John Doerr's Measure What Matters and are a demonstration of how OKRs should cascade down an organization.

OKR Chart #2 from John Doerr's Measure What Matters

OKR Chart #3 from John Doerr's Measure What Matters

Best practices

The best practices listed below are taken directly out of John Doerr's Measure What Matters.

"The objective is the direction: “We want to dominate the mid-range microcomputer component business.” That’s an objective. That’s where we’re going to go. Key results for this quarter: “Win ten new designs for the 8085” is one key result. It’s a milestone. The two are not the same…

The key result has to be measurable, so that at the end you can look and without any arguments ask: Did I do that or did I not do it? Yes? No? Simple. No judgments in it.

Now, did we dominate the mid-range microcomputer business? That’s for us to argue in the years to come, but over the next quarter we’ll know whether we’ve won ten new designs or not."

The essence of a healthy OKR culture is ruthless intellectual honest, a disregard for self-interest, deep allegiance to the team.

Here are some of the lessons from Intel, Andy Grove and Jim Lally (Andy’s OKRs disciple):

Less is More.

“A few extremely well-chosen objectives,” Grove wrote, “impart a clear message about what we say ‘yes’ to and what we say ‘no’ to. A limit of three to five OKRs per cycle leads companies, teams and individuals to choose what matters most. In general, each objective should be tied to five or fewer key results.

Set goals from the bottom up

To promote engagement, teams and individuals should be encouraged to create roughly half of their own OKRs, in consultation with managers. When all goals are set top-down, motivation is corroded.

No Dictating

OKRs are a cooperative social contract to establish priorities and define how progress will be measured. Even after company objectives are closed to debate, their key results continue to be negotiating. Collective agreement is essential to maximum goal achievement.

Stay Flexible

If the climate has changed and an objective no longer seems practical or relevant as written, key results can be modified or even discarded mid-cycle.

OKRs are adaptable by nature. They’re meant to be guardrails, not chains or blinkers.

As you asses and audit OKRs within a cycle, you have four options:

Continue: If a green zone (“on track”) isn’t broken, don’t fix it.

Update: Modify a yellow zone (“needs attention”) key result or objective to respond to changes in the workflow or external environment. What could be done differently to get the goal on track? Does it need a revised time line? Do we back-burner other initiatives to free up resources for this one?

Start: Launch a new OKR mid-cycle, whenever the need arises.

Stop: When a red zone (“at risk”) goal has outlived its usefulness, the best solution may be to drop it.

These events might be result during CFRs, a Post-Mortem or one of the scrum key ceremonies, such as a sprint review, sprint retrospective, backlog grooming session; or after receiving client/customer feedback.

Dare to Fail

“Output will tend to be greater,” Grove wrote, “when everybody strives for a level of achievement beyond [their] immediate grasp… Such goal-setting is extremely important if what you want is peak performance from yourself and your subordinates.” While certain operational objectives must be met in full, aspirational OKRs should be uncomfortable and possible but not unattainable.

“Stretched goals” as grove called them, push organizations to new heights.

A Tool not a Weapon

The OKR system, Grove wrote, “is meant to pace a person – to put a stopwatch in his own hand so he can gauge his own performance. It is not a legal document upon which to base a performance review.” To encourage risk taking and prevent sandbagging, OKRs and bonuses are best kept separate.

Be Patient, Be Resolute

Every process requires trial and error. As Grove told his iOPEC students, Intel “stumbled a lot of times” after adopting OKRs: “We didn’t fully understand the principal purpose of it. And we are kind of doing better with it as time goes on.” An organization may need up to four or five quarterly cycles to fully embrace the system, and even more than that to build mature goal muscle.

Looking to learn more about Project Management, Technology and Strategy?

Search our blog to find educational content on project management, design, development and strategy.